It should also have made him, given his native intelligence and musicality, a natural performer of those works, and indeed he could, in the lecture room, play difficult passages in Liszt or Schumann with careless ease. That meant Rosen learning the core repertoire from Bach to Brahms pretty well by heart, and it was that lifelong sensuous contact with the great canonical works, so that they were felt under the fingers as well as analysed by the mind, that was the key to making Rosen the great critic that he would later become. Rosenthal, a pupil of Liszt, had gone to the US after the Anschluss joining Austria to Germany, and he – together with his wife, a notable teacher who continued to guide Rosen into his 20s – impressed on him the necessity to acquire a wide musical culture rather than focusing narrowly on a few works. However, by the time he was 11, his playing of Beethoven impressed the great Moriz Rosenthal sufficiently for him to take Rosen on as a pupil.

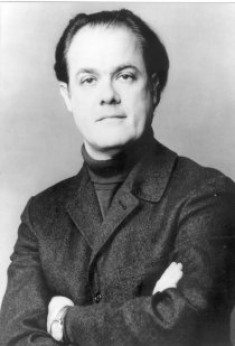

Although Rosen, born in Manhattan, New York, to an architect father and a mother who played the piano, started lessons on the instrument at the age of three, and enrolled at the Juilliard school when he was seven, he was no child prodigy. Such all-round brilliance is not acquired quickly.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)